Monsters of Music?: Wagner, Strauss, and The Third Reich

From Dennis Neil Kleinman, host of The Opera Connection

Whenever I host The Opera Connection, I like to start with a game I call, “What’s The Connection?” I show two pictures side by side and ask attendees what the connection is between them. Most often, it will be two composers or two operas. (But not always. I once showed a still of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, opera’s most notorious lothario, next to one of Donald Trump. Not surprisingly, the reactions split along party lines.)

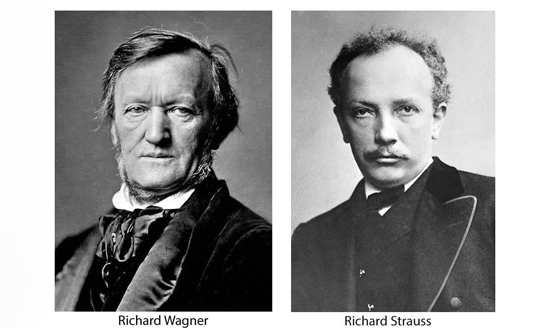

The reason I mention it is that I have two Opera Connections coming up right in a row and there is an intriguing, one might say sinister, connection between the composers of those operas. The first is Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin on Saturday, April 22. The second, Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier the following Sunday, April 30. Can you guess the connection? (Hint: It’s not that both composers are named Richard.)

The connection is that both of these composers are linked in the minds of many with Nazism. So here are two questions this article will attempt to answer: 1) Is this taint on their legacy justified?, and 2) If question 1 is true, should their music be shunned? As an opera lover who happens to be Jewish, these two questions are: 1) especially resonant, and 2) pertinent because of the current political turmoil in our country.

The first of the two questions should be a slam dunk, at least in Wagner’s case. He died in 1883, half a century before the Nazis came to power, so it would be temporally impossible for him to have had any direct contact with the Nazis. He did, however, have a direct impact on the Nazi movement. Wagner was a notorious anti-semite, and his high standing in 19th Century culture gave him a prominent platform from which to deliver his racist screeds. Meanwhile, back at the Wagner manse, his wife Cosima, who was even more rabid in her anti-semitism than her husband, made sure that the Wagner kids and grandkids carried on the family tradition.

By the time the Nazi’s came to power in 1933, the Wagner clan’s anti-semitic creds were so well-established that Hitler took time out from his busy schedule to ingratiate himself with the family. And, to make sure that Wagner’s influence continued uninterrupted, he saw to it that his operas were continuously performed, even as the Third Reich was going down in flames.

Richard Strauss, on the other hand, was alive and well when the Nazis took power. While his reputation as the most thoroughly ‘modern’ composer of his time had slipped somewhat from the heady days of Der Rosenkavalier, he was still a highly respected international figure, someone the Nazis wanted to have on their side.

He was offered the position of president of the Reichsmusikkammer, the government bureau which had jurisdiction over all musical matters. Strauss, who was hardly immune to flattery and whose views synced up pretty well with the early Nazis regime, accepted. But Strauss never actually joined the Nazi party; he saw himself, as a great artist, above the political fray.

There are those who have accused Strauss of being an opportunist. But there is ample evidence that there was something he was not: an anti-semite. Two persuasive pieces of evidence to back this up. The first is that his son married a Jewish woman who Strauss became very fond of. After the war, Strauss claimed that he played footsie with Hitler in order to keep his daughter-in-law and grandchildren out of the camps. (There is evidence that she survived the war due to Strauss’s efforts.) The second is his refusal to stop working with his Jewish librettist, Stefan Zweig, even when the authorities strongly suggested he stop. (For this grievous sin he was removed from his position at the Reichsmusikkammer.)

So Wagner, who wasn’t a Nazi, was, however, an anti-semite who influenced Hitler and whose progeny carried on his noxious legacy. Strauss, who wasn’t anti-semitic, carried water for the Nazi’s for self-serving as well as altruistic reasons. The historical record does not exonerate either composer. But if I had to choose which of these men should “geht a gehena” (Yiddish for “Go to Hell”) I would say that Wagner gets the nod.

Now for the second question: “Should their music be shunned?” I believe this question applies more to Wagner than Strauss for the reasons stated above. Even if one is inclined to condemn him for the Nazi foot-play, almost all of the works by Strauss that are still performed were written well before the Nazi’s rise to power, and none of those works have anti-semitic texts. As far as listening to Strauss’ music is concerned, I say “gezunterheit!” (Yiddish for ”Knock yourself out!”)

Wagner is a whole other kettle of worms. He was vociferously anti-semitic, and laid at least some of the groundwork for the Nazi nightmare to come. But to say that listening to Wagner’s music makes one feel more antisemitic is pushing it. Music just isn’t that specific. Another anti-listening-to-Wagner argument is that some of the villainous characters in his operas have what would have been considered Jewish traits to Wagner’s audience. But there is never an explicit reference to Jews in them, so it is in the eye and ear of the beholder as to whether one views them that way.

The final argument for shunning Wagner’s music is perhaps the most compelling: Does enjoying his work translate to an endorsement of the man and all that he stood for? A modernized version of this dilemma surrounds Harvey Weinstein: Does his atrocious behavior mean that we should shun every movie he ever produced, a list that includes some of the finest films of the late 20th century? A tough question, and one that many cinefiles are still grappling with.

So where does that leave me, the opera-loving Jewish guy? In an uncomfortable position. I love Wagner’s music. Not all of it. Some of it is just too longwinded, to my ears at least. But when it is good, there is absolutely nothing as exhilarating or enthralling. And, though I am well aware of the monster behind the music, I still listen. But with anti-semitism on the rise in the U.S., and with the truism “It can’t happen here,” sounding less and less true, my listening habits may be changing.